Keyboards and Consoles

|

The first part of an organ that many people see, and the only part that is visible in some installations, is that part of the instrument that contains the keyboards. Two names are used for this component:

The term "keydesk" is used when the keyboards are found attached to the main case of an organ. This is the typical placement for keyboards in organs that use mechanical action, but other instruments may be built with this placement as well.

The simplest consoles and keydesks have only keyboards and stop controls for the organist to use. Additionally, either may contain other elements which serve as playing aids to the organist. The following are included in this group of components:

Even when all these elements are included in a console or keydesk, they may take on a different appearance from instrument to instrument. Consider these two photographs:

The photograph to the

right

shows the console of a large instrument

62 built with electro-pneumatic action. It is detached

from the rest of the

organ, which is visible in this installation only in part and that through various

screens placed to

conceal it.

The photograph to the

right

shows the console of a large instrument

62 built with electro-pneumatic action. It is detached

from the rest of the

organ, which is visible in this installation only in part and that through various

screens placed to

conceal it.

The

photograph to the left is

of the keydesk of an instrument built with mechanical action.

63 The keyboards are built into

the main case, which houses the rest of the organ, including the blower, reservoir,

chests and

pipes.

The

photograph to the left is

of the keydesk of an instrument built with mechanical action.

63 The keyboards are built into

the main case, which houses the rest of the organ, including the blower, reservoir,

chests and

pipes.

.

The most consistent element is found in the keyboards, which have some similarity to those found on pianos, systhesizers, and similar instruments. Other elements, including stop controls, present somewhat different appearances in the photographs, but in function they are similar if not identical. The sections below include detailed descriptions of keyboards and stop controls, and a brief description of the more common playing aids which are found on late twentieth-century organs in the United States. Photographs illustrate the different forms each may take, and their functions are described from the standpoint of their use by the player, not from the standpoint of the hidden mechanics.

Organs in the United States typically have two different types of keyboard.

Manual keyboards, usually called simply "manuals," are played with the hands and fingers (hence the name). Some instruments may have black and white keys, as on most pianos, but others may have keys covered with woods of different colors, bone, or several other natural or synthetic substances.

During the nineteenth century piano keyboards expanded in range to reach the current standard: 88 keys. The standard 19 organ manual in the US has only 61 keys, and 56- or 58-note manuals are more common than they were in 1950. On almost all organs built in the twentieth century, the lowest key is C, corresponding to the C two octaves below middle C. When the keyboard has a full range of 61 notes, the highest key is also C, three octaves above middle C. In the case of shorter range keyboards, the top note is either G or A below that C, for 56-note and 58-note keyboards respectively.

In the United States,

two-manual or three-manual organs are most common, but historically,

organs have been built with any number from one to seven manuals. The photograph to

the right

shows a view of a three-manual console.

66 The manuals have a 61-note

compass, with natural keys covered with bone and sharps made of rosewood.

In the United States,

two-manual or three-manual organs are most common, but historically,

organs have been built with any number from one to seven manuals. The photograph to

the right

shows a view of a three-manual console.

66 The manuals have a 61-note

compass, with natural keys covered with bone and sharps made of rosewood.

The photograph to the left

shows a similar view of a three-manual keydesk.

67 The manuals have a 58-note

compass, with naturals covered with ebony and sharps made of rosewood with ivory

caps.

The photograph to the left

shows a similar view of a three-manual keydesk.

67 The manuals have a 58-note

compass, with naturals covered with ebony and sharps made of rosewood with ivory

caps.

Pedal keyboards, usually called "pedalboards," or more simply "pedals," are played with the feet (again, that should explain the name). Though manuals follow a common plan, in that they are flat and have keys that are parallel to one another, pedalboards may be designed and built in one of several ways. The primary distinguishing features are determined by two variables:

Although there are other possibilities for combining these two variables, only two are common in organs in the United States.

In the photograph to the

right, the concave shape can be seen most clearly in the line formed by the sharp

keys and the

front of the pedalboard.

67

The keys are also closer together in the back than they are in the

front as a

result of the radiating design and placement of the individual keys.

In the photograph to the

right, the concave shape can be seen most clearly in the line formed by the sharp

keys and the

front of the pedalboard.

67

The keys are also closer together in the back than they are in the

front as a

result of the radiating design and placement of the individual keys.

Although an organ can be made with only one stop, such instruments are quite uncommon. Most organs have several ranks of pipes in each division, and stop controls allow the organist to select which ones will sound when the organ is played.

In appearance and placement, stop controls are largely of two types:

Drawknobs actually illustrate the origin of the term "stop." The wind supply to a rank of pipes is literally "stopped" when the drawknob is pushed in. Modern usage has reversed this, though, and most players think of turning a stop on when the drawknob is pulled out. The actions and results are the same in both cases.

Drawknobs vary in appearance only slightly from one instrument to another.

Drawknobs are almost always found on instruments in which the stop action itself is mechanical. In such organs, the drawknob is an extension of a rod that connects to a slider through a trundle, a device that works like a combination of rollers, stickers and trackers. Drawknobs are also used on organs with electric actions of one type or another. The usual placement of drawknobs in these instances is to the side of the keyboards, and there are two different patterns that may be followed in their placement in groups.

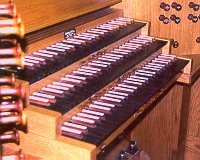

The photograph to the right

shows one system for grouping drawknobs. Those that control the stops of a given division are

arranged in columns.

The three groups here are Pedal and Manual II (Brustpositiv) to the left of the

keyboards, and

Manual I (Hauptwerk) to the right. In most installations, standard placement

further groups the

drawknobs of a given division:

The photograph to the right

shows one system for grouping drawknobs. Those that control the stops of a given division are

arranged in columns.

The three groups here are Pedal and Manual II (Brustpositiv) to the left of the

keyboards, and

Manual I (Hauptwerk) to the right. In most installations, standard placement

further groups the

drawknobs of a given division:

Although this formula for placing stops is the current standard supported by the

American Guild

of Organists,

65 it is not strictly followed on every instrument. Often

drawknobs are

grouped so that stops that might be used together are close to one another. This

arrangement

facilitates making stops changes during performances.

A second system for

placement

of drawknobs is found on "terraced" consoles and keydesks, as seen in the photograph

to the left.

In this type of placement, drawknobs extend horizontally to each side of the keyboard

that is

associated with the division that it controls. In the photograph knobs on the top

row control

stops for the fourth manual (counting up from the lowest one), the next for the

third, and so on

down the list. The bottom row of knobs control stops of the pedal division.

A second system for

placement

of drawknobs is found on "terraced" consoles and keydesks, as seen in the photograph

to the left.

In this type of placement, drawknobs extend horizontally to each side of the keyboard

that is

associated with the division that it controls. In the photograph knobs on the top

row control

stops for the fourth manual (counting up from the lowest one), the next for the

third, and so on

down the list. The bottom row of knobs control stops of the pedal division.

When drawknobs are

used as stop controls on organs that do not have a mechanical connection to the

chest, they are

usually placed in one of the two arrangements described above. If the system of

vertical groups is

used, the drawknobs are usually placed on jambs that are at an angle to the line of

the keyboards.

In the photograph to the right, two stops in the third column are drawn, i.e., they

are in the "on"

position.

When drawknobs are

used as stop controls on organs that do not have a mechanical connection to the

chest, they are

usually placed in one of the two arrangements described above. If the system of

vertical groups is

used, the drawknobs are usually placed on jambs that are at an angle to the line of

the keyboards.

In the photograph to the right, two stops in the third column are drawn, i.e., they

are in the "on"

position.

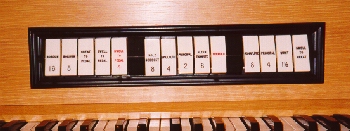

Tilting tablets or stop keys are often used in consoles of electric-action instruments. Although they may be placed on side jambs as are drawknobs, they are more often arranged in rows above the manuals. The tablets or stop keys are positioned so that the stops of a single division are placed together. Within the stops of a division, the same order is followed that appears above, but placement reads from left to right, rather than from lowest to highest in a column:

The photograph to the right

shows the full set of stops for a very small two-manual organ. The first group of

stops controls

the Pedal, the second a small Swell, and the third the stops of the Great. Controls

for couplers

(see below) are located along with the stops of each division.

70

The photograph to the right

shows the full set of stops for a very small two-manual organ. The first group of

stops controls

the Pedal, the second a small Swell, and the third the stops of the Great. Controls

for couplers

(see below) are located along with the stops of each division.

70

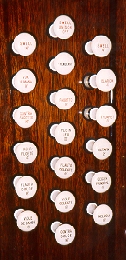

In some cases, names of different types stops will be

engraved in different colors, or a

different color may be used for the background material of a stop tab or tilting

tablet. The photograph to the left

shows stop controls from an instrument in which stop names of flues are printed in

black on

white, stop names of reeds are printed red on white, and names of couplers (see

below) are

printed white on black.

100

In some cases, names of different types stops will be

engraved in different colors, or a

different color may be used for the background material of a stop tab or tilting

tablet. The photograph to the left

shows stop controls from an instrument in which stop names of flues are printed in

black on

white, stop names of reeds are printed red on white, and names of couplers (see

below) are

printed white on black.

100  The stop tablets in the photograph to the right have a

wooden veneer that matches the

finish of the console.

101 Regardless of their specific appearance, stop

tablets and tilting tablets

consistently work by turning a stop on when the tablet is pushed down and turning it

off when the tablet is raised.

The stop tablets in the photograph to the right have a

wooden veneer that matches the

finish of the console.

101 Regardless of their specific appearance, stop

tablets and tilting tablets

consistently work by turning a stop on when the tablet is pushed down and turning it

off when the tablet is raised.

Although it is possible for an organ to be made with only keys and stop controls in the keydesk or console, almost all organs in the United States have been equipped since the nineteenth century with other mechanisms. These additional devices are often grouped under the heading "console accessories," but after so many years of use, most organists consider them essential parts of an instrument. Some of these have a long history, while others are relatively new in that they did not exist before the twentieth century and the widespread use of electricity. The most common additional components - - "playing aids" or "accessories" - - are described below.

Couplers have the longest history of any of the additional components of an organ. Since at least the seventeenth century, they have allowed the organist to play the stops of one division from a second keyboard. In later applications, they allowed a key to play any stop an octave above or below the key being played. Because couplers are most often engaged or activated by controls that are included with stop controls, they are sometimes referred to as "non- speaking stops." They control no pipes, and if no other stop is drawn - - other than a coupler - - no sound is made when they are played.

Couplers are often divided into two groups according to function. Couplers of each type are often included on organs built in the United States in the twentieth century.

The controls for couplers are usually of two types as well.

In organs with

mechanical stop action, couplers are often engaged with controls that must be "hooked

down" to

engage the coupling action. These are usually placed on a panel above the pedalboard

- - the

"kneeboard." These controls have a spring attached to them that holds the control in

the upper

position so that the coupler is usually not engaged. When the control is pressed

down, the

coupler action engages. An L-shaped opening in the kneeboard allows the control to

be moved to

the side so that the spring cannot return it to the off position until it is moved

again by the

organist.

In organs with

mechanical stop action, couplers are often engaged with controls that must be "hooked

down" to

engage the coupling action. These are usually placed on a panel above the pedalboard

- - the

"kneeboard." These controls have a spring attached to them that holds the control in

the upper

position so that the coupler is usually not engaged. When the control is pressed

down, the

coupler action engages. An L-shaped opening in the kneeboard allows the control to

be moved to

the side so that the spring cannot return it to the off position until it is moved

again by the

organist.

In the photograph above, three hook-down couplers can be seen above a

pedalboard. The third one is in the "on" position. It is engaging a coupler that

permits stops on

Manual I to be played by the pedal. Felt is placed along the edges of the opening in

the

kneeboard to absorb sound that might be made as the coupler is engaged.

Expression pedals

have also been a part of organ consoles and keydesks in the United

States since the nineteenth century. They are placed above the pedalboard and are

inset in the

kneeboard. Expression pedals are used

to open and close shades that

enclose the pipes of a given

division. Because expression

pedals are most often associated with Swell

divisions, they are often called "swell

pedals," which can be

confusing when they are used to adjust the position of shades in an enclosed Choir or Solo

division. Another name that is

often used is "swell shoe," a term that carries the same possibility for confusion

with the Swell

division, but avoids any confusion with references to pedal keys. The photograph to

the right

shows the kneeboard, part of the pedalboard, and a swell pedal of a small organ with

a single

enclosed division.

84

Expression pedals

have also been a part of organ consoles and keydesks in the United

States since the nineteenth century. They are placed above the pedalboard and are

inset in the

kneeboard. Expression pedals are used

to open and close shades that

enclose the pipes of a given

division. Because expression

pedals are most often associated with Swell

divisions, they are often called "swell

pedals," which can be

confusing when they are used to adjust the position of shades in an enclosed Choir or Solo

division. Another name that is

often used is "swell shoe," a term that carries the same possibility for confusion

with the Swell

division, but avoids any confusion with references to pedal keys. The photograph to

the right

shows the kneeboard, part of the pedalboard, and a swell pedal of a small organ with

a single

enclosed division.

84

Combination pistons are used to make rapid stop changes from the console, and are found only on organs with electric stop action. When activated they physically move the stop controls, whether they are in drawknob, tilting tablet, or stop key form. They take two forms:

Thumb pistons are located on

the keyslips - - the panels below manual keyboards. Most instruments have pistons

that affect

only the stops of a single division, as well as those that affect all the stops on

the organ. The

latter are called "general pistons," while those that affect only the stops of a

single division are

called "divisional pistons." The appearance of thumb pistons varies. Those in the

photograph to

the right are the most common shape - - round buttons.

102

The ones shown here are dark in color, but white or ivory-colored thumb pistons are

perhaps more common.

Thumb pistons are located on

the keyslips - - the panels below manual keyboards. Most instruments have pistons

that affect

only the stops of a single division, as well as those that affect all the stops on

the organ. The

latter are called "general pistons," while those that affect only the stops of a

single division are

called "divisional pistons." The appearance of thumb pistons varies. Those in the

photograph to

the right are the most common shape - - round buttons.

102

The ones shown here are dark in color, but white or ivory-colored thumb pistons are

perhaps more common.

Pistons that can be operated by the feet are located above the pedalboard and are usually called toe studs. They are larger than thumb pistons, but may also be divided so that some of them affect only the pedal stops, while others affect the entire organ. The AGO standard places general pistons to the left of the expression pedals, pedal divisional pistons to the right. Photographs of different designs for toe studs can be seen below, after the description of crescendo pedals.

Several other features of pistons are worth noting:

A Register Crescendo Pedal, usually called a "crescendo pedal," adds stops one at a time in a pre-determined order. A crescendo pedal is located to the right of expression pedals, and is usually built like them.

The appearance of toestuds (both combination pistons and reversibles) and expression and crescendo pedals can vary from one instrument to the next. Two examples can illustrate the range of the variation to be found in these common console accessories.

The photograph to the right

shows part of a console that

has

The photograph to the right

shows part of a console that

has

The photograph to the left shows a similar view of a different console.

The photograph to the left shows a similar view of a different console.