New Orleans: Felicity Methodist

|

IntroductionFelicity United Methodist Church is located at the eastern edge of the historic Garden District of New Orleans, in an area that might best be described as a "declining neighborhood." According to a plaque on the side of the building, the church's first structure was built in 1850, but was destroyed by fire in 1887. The present building -- which has not escaped damage from the periodic hurricanes that assail Louisiana's coastal region -- was built the following year.231 The interior of the building has been modified several times, occasionally as the result of repairing hurricane damage, occasionally in attempts either to modernize the building or to introduce some economical changes. When you look at the ceiling, for example, you will see a flat, hard surface, and you would be correct to think that it contributes to the lively acoustic of the room. That flat, hard surface is the third ceiling in the room, however, replacing a suspended ceiling that had been installed in an effort to reduce heating and cooling costs.

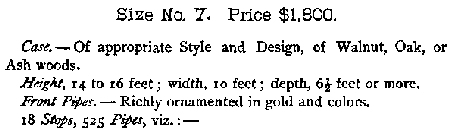

Catalog DescriptionThe organ in Felicity Methodist is one of Hook's "Size No. 7" instruments, as listed and described in a brochure of around 1881. Here's the general description from page 4 of that publication:230

The photograph to the right shows more clearly that the pipes are stencilled -- "richly ornamented," in the language of the brochure. The pattern of the stencilling (which has not been refurbished in this organ, but is original) is perhaps plainer than you might find in other "Size No. 7" organs, but the choice of a simple geometric border can be considered an element of "appropriate style," to use the words of the brochure again. You can also see in this photograph that the decorative elements of the case itself are minimal. The wooden structures at the sides of the pipes are quite plain, and only the cross piece -- which is placed at the same level as the top of the case behind the pipes -- has any carving or molding on it. The Keydesk

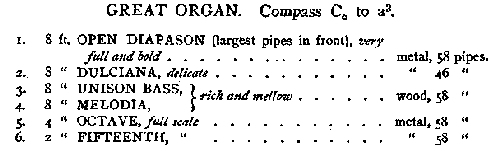

The StoplistThe description says the instrument has "18 Stops," and the rest of the page in the brochure itemizes eighteen items controlled by stop knobs. I've rearranged them slightly in this stoplist, not so I could "correct" anything, just to be consistent in the way we look at such lists.

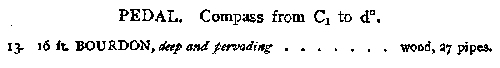

Of course, you wouldn't expect a builder today to include the Tremolo or couplers in a stop count, but that was not unusual for the nineteenth century. The "Bellows Signal," which was originally used to tell the assistant to start pumping, can be seen as the equivalent of a blower switch, and we wouldn't count that either. The thirteen remaining stops, however, represent only 10 ranks of pipes. In the stoplist above, I've included the number of pipes controlled by each stop -- and they do add up to 525 pipes, just as the brochure promises. The single pedal stop is a "full-compass stop," and as such it has one pipe for each key of the pedalboard. Those manual stops that have 58 pipes are also full-compass stops, so that every note on the appropriate manual has a matching pipe in each of those stops. Some of the manual stops have only 46 pipes, however, and I've marked those with an editorial TC (for "tenor C") in brackets. Their 46 pipes begin at the second C of the manual keyboards, so they don't play in the first, or bass octave. The two "Stopped Bass" stops, however, play only in the first octave, as does the Bassoon. As you will see in the brochure description below, you might find similar divided stops called "Unison Bass" or "Common Bass," and in general, these stops control the bottom octave of a stopped flute -- the Melodia and Stopped Diapason in this case. The first twelve pipes are provided with a second stop knob so that you can use them as the bass pipes for the other short-compass stops -- the Dulciana and the Viola. Stops that are divided at this point -- at c rather than c' -- are provided chiefly for economic reasons. In the first place, the large 8' open pipes of the two associated stops (the Dulciana and the Viola) are not present, so there is a savings in the construction, packing and shipping of twenty-four of the largest pipes of the organ. Secondly, there is a savings in height. Look again at the stoplist. In the swell, there is no pipe over 4' long. The longest pipe of the Stopped Diapason is only 4' long, and the Bassoon is half-length in the bottom octave. On the Great, only the 8' Open Diapason extends to a full 8' octave. As we have seen above, those pipes are not contained in the case, they extend beyond its top. The second economic factor is then in a savings in height. Less space is required for the pipes themselves, so there is a savings in both materials and work in producing the case. All in all, "Size No. 7," or a similar design by another builder, was an economical choice for a church in the 1880's, providing a great deal of flexibility with a small number of registers. Tonal CharacteristicsWe can take another look at the catalog description of the "Size No. 7" organ and get a general idea of the sound of this organ -- or of what the firm wanted you to think was the sound of the organ.

According to this description the sound of the Open Diapason is "very full and bold," but there is no description of the sound of the Octave or the Fifteenth. We are just told they are "full scale." Actually, the Diapason is of average scale, with a normal mouth width and cut-up for a principal. There is no excessive nicking, and the sound is indeed a full one, rich in harmonic development. The Octave and Fifteenth have a complementary sound, and the three together form a very convincing basic chorus. The first twelve pipes of the Melodia carry a different name on the stop knob than they have here in the brochure. They are, in fact, stopped wooden pipes, and they have the dark quality you would expect to hear. The rest of the Melodia is of open metal pipes that are harmonic above c'''. The sound is a full, rich, and colorful as you would expect from such a stop. In contrast, the Dulciana is quite soft -- "delicate" -- and has the balance between fundamental and overtones you expect in a principal.

There is no principal stop on the Swell, and that's typical of small organs from this period. The string -- in the case of the Felicity organ a Viola -- is perhaps more "delicate" than "crisp," with a sound that is equal in dynamic level to the Dulciana. The Viola is small in scale, and its color is definitely that of a string, not a principal. The Stopped Diapason forms a similar parallel to the Melodia of the Great. The sound is similar in volume, but contrasting in color, and each of them has a distinct character in its timbre. The two harmonic flutes (the Melodia on the Great and the 4' Flute Harmonique on the Swell) also have distinct voices, that of the Swell being lighter and less commanding than the Great. The Oboe-Bassoon -- another divided stop -- is a small trumpet in both construction and sound, and this gives it a great deal of flexibility in such a small instrument. You can use it as a solo stop in the treble, while the Stopped Bass is coupled to the Pedal and you play the accompanying voices on the Dulciana. In contrast, you can use the same stop in the chorus by coupling it to the Great.

The Pedal stop of the Felicity organ is a 16' Bourdon, just what you would expect to find on a small instrument. Made of wood, the stop is voiced to provide the maximum degree of fundamental pitch from such pipes. It can be used under the chorus of the Great as well as it can to provide a bass for the Dulciana or Stopped Diapason. The divided stops give an additional choice for coupling 8' stops to the pedal -- provided, of course, you don't play above the first octave. ConclusionAll in all, the Felicity Methodist Hook and Hastings organ is quite typical of the builder's work in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The principals are traditional in scale and voicing, even though other builders were moving toward larger scales, more pronounced nicking, and a more fundamental, less colorful sound. On the other hand, the Melodia on the Great is a "sign of the times," included here as a replacement for the Clarabella of the earlier E. & G. G. Hook organs. The Dulciana is quieter than similar stops of a half-century or more earlier, while the Oboe is a compromise between a solo stop and a chorus reed. Altogether, this is a successful organ for its size, and the sound it produces in the room is rich, full, and exciting. © 2001 James H. Cook |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The organ was installed when the present building was completed, replacing an earlier E. & G. G. Hook & Hastings organ that had been lost in the fire the year before. The organ stands in its original position in the center of the church, as you see in the photograph to the left. You can also see how the new ceiling and accompanying grill have cut off the tops of the first few diapasons. The instrument has not been modified since its installation, other than having an electric blower added. The "new" organ presents a puzzle, however, because some of the pipes and other parts are marked as being from Hook's op. 1269, but the instrument itself is op. 1366. Apparently the earlier instrument had never been installed, and the company re-used some of the parts in the organ for Felicity Methodist.

The organ was installed when the present building was completed, replacing an earlier E. & G. G. Hook & Hastings organ that had been lost in the fire the year before. The organ stands in its original position in the center of the church, as you see in the photograph to the left. You can also see how the new ceiling and accompanying grill have cut off the tops of the first few diapasons. The instrument has not been modified since its installation, other than having an electric blower added. The "new" organ presents a puzzle, however, because some of the pipes and other parts are marked as being from Hook's op. 1269, but the instrument itself is op. 1366. Apparently the earlier instrument had never been installed, and the company re-used some of the parts in the organ for Felicity Methodist.

In the photograph above, you can see some of these characteristics listed here. The organ is located in a case, even though the front pipes extend upward beyond its top. That particular element of case design was typical for that period. Although many other builders would not have included a full case over any of the pipes of the Great, Hook & Hastings generally built a full case -- including the top -- over all but the 8' Open Diapason in instruments of this size.

In the photograph above, you can see some of these characteristics listed here. The organ is located in a case, even though the front pipes extend upward beyond its top. That particular element of case design was typical for that period. Although many other builders would not have included a full case over any of the pipes of the Great, Hook & Hastings generally built a full case -- including the top -- over all but the 8' Open Diapason in instruments of this size.  In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Hook's small organs were typical of the period not just in their stoplists, but in other ways as well. Such instruments had slider chests and straight mechanical action for both keys and stops, with no pneumatic assists required. Keydesks were normally attached, so complications arising from a detached console could be avoided. The stops for the Swell are arranged on the jambs to the left of the manuals, those of the Gread and Pedal on the rght, much as you might expect to find in console built to AGO standards today. The couplers are also controlled by drawknobs on either side.

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Hook's small organs were typical of the period not just in their stoplists, but in other ways as well. Such instruments had slider chests and straight mechanical action for both keys and stops, with no pneumatic assists required. Keydesks were normally attached, so complications arising from a detached console could be avoided. The stops for the Swell are arranged on the jambs to the left of the manuals, those of the Gread and Pedal on the rght, much as you might expect to find in console built to AGO standards today. The couplers are also controlled by drawknobs on either side.  The manual compass is 58 notes, C to a''', a common standard for the time. The pedalboard is both straight and flat. Even though Hook had built Willis-type curved radiating pedals even as early as the 1850's, they could build the simpler straight pedals more efficiently, a factor that enabled them to offer lower prices on these instruments. Another common element of the time can be seen in the placement of the swell shoe to the right of the keyboard, where its mechanism would not interfere with the trackers that formed part of the coupler mechanism between manual and pedal. You can see this placement even better in the photograph to the right.

The manual compass is 58 notes, C to a''', a common standard for the time. The pedalboard is both straight and flat. Even though Hook had built Willis-type curved radiating pedals even as early as the 1850's, they could build the simpler straight pedals more efficiently, a factor that enabled them to offer lower prices on these instruments. Another common element of the time can be seen in the placement of the swell shoe to the right of the keyboard, where its mechanism would not interfere with the trackers that formed part of the coupler mechanism between manual and pedal. You can see this placement even better in the photograph to the right.