Hook and Hastings

|

|

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the Hooks had a thriving business, one that was growing even as the country became embroiled in its internal struggle to remain a Union. As their business expanded, they admitted Frank Hastings as a partner, and after 1870, the firm was known first as E. & G. G. Hook and Hastings, later -- after the deaths of both Elias and George Hook -- as Hook & Hastings.232 Along with instruments by other builders of the time, their organs evolved in tonal, mechanical and visual design, gradually taking on new characteristics. In the years following the Civil War, American musicians looked toward Europe for their models as they developed a musical establishment of their own. Organ builders were a part of this process, and instruments built by the Hooks soon began to include traits derived from English, French, and German organs. Throughout this period, however, and in large part through the very act of incorporating elements from different traditions, their instruments became at the same time more "American," without ever losing the elements that revealed their English origins. LocationOne of the changes that occurred in Hook organs can be seen in the locations in which you will find their instruments. The opus list the firm published in 1895, for example, is a chronological listing of their instruments.220 If you look at this list starting in 1860, you'll see right away that they began to build organs for places other than churches or synagogues. The list indicates two instruments were built for Masonic Halls in 1860 (New Bedford and Lawrence, Massachusetts), and in 1864, one of their extant and most well-known organs was installed in Mechanics' Hall, Worcester. This move toward building "civic organs," or "auditorium organs," was in keeping with trends throughout the nation and the industry. As industrial centers throughout the country became more stable through the later nineteenth century, and as a developing cultural life became more widespread, urban centers became more and more distinguished by their musical institutions. Part of this distinction was the provision of theaters, concert halls, and civic auditoriums, and an organ was considered a necessary part of these buildings. Another aspect of the "location" of organs in the late nineteenth century concerns their relocation within church buildings. Earlier, organs were most often placed in a rear gallery large enough to hold both the instrument and a choir. During the last third of the century, there was a gradual move toward placing both the choir and the organ in the chancel area. In a way, we can look at this move as signalling the end of the "visible organ," at least for a time, because the elegantly decorated pipes that were so much a part of the times were not always seen as being "proper" for the chancel. They provided a large, often distracting visual display that begged for the parishioners' attention. The solution -- unfortunately aided by the development of mechanisms more flexible than direct tracker action -- was to move the organ into chambers, out of sight of the congregation. Although this removal of the pipes from view would not be completed until the early years of the twentieth century, the first steps were taken when the organ left its high position in the rear gallery and moved to the floor level of the chancel. DispositionIn the first paragraph at the top of this page, I made the statement that builders in the late nineteenth century developed an instrument that became distinctly American in its eclecticism. One of the first places you should look for evidence of change is, of course, in the dispositions. The typical three-manual organ of the late nineteenth century still had the three basic manual divisions that it derived from its English parent, and the Swell -- the distinctive English division -- was the second most important division of the instrument. The continued emphasis on the Swell over a Choir or Positiv division remains a trait of American organs even today. You can also find the English origin of the nineteenth-century American organ in the names of the primary stops of the Great, because Open Diapasons, Principals, Twelfths and Fifteenths are always there. But other stop names began to appear with more and more regularity, some of them new creations, but others taken from European traditions. One example is the inclusion of harmonic flutes, built in the style of Cavaillé-Coll Flûtes harmoniques. Although the Hooks had established the Clarabella as the "signature" 8' flute on the Great of their earlier organs, you will find the Harmonic Flute replacing it on later instruments. Even when the stop has a different name -- Melodia, for example -- the upper octaves of the 8' flute on the Great will be harmonic in construction. You will be able to recognize the origin of many of these stops, even though their names might contain peculiarly "Americanized" spellings. For example, you'll have no trouble reading "Doppelflute" and knowing it's a modified form of Doppelflöte, or knowing "Flute Harmonic" is Flûte harmonique. You might wonder, however, about a stop called a "Clariana," and a "Labial Oboe" might puzzle you for a while. As you read the stoplists of Hook & Hastings organs, as well as late nineteenth-century by other builders, look for these and other examples of appropriation and invention in expanding the possibilities in American dispositions. The other change that occurs in dispositions of the late nineteenth century is an increasing emphasis on the fundamental. The first sign you see is the gradual disappearance of higher-pitched stops. Beginning with the "least important" division (the Choir), moving to the Swell, continuing to the Great, builders omit mixtures from stoplists. They are replaced with additional stops at 8' pitch, and you will see quite late in the century another appropriation from English builders when American organs start to include two or more open diapasons on a single division. After 1860, Hook -- along with virtually all other American builders -- stopped building the short-compass Swell, so all manual divisions were full-compass, beginning on C. At about the same time, they adopted the 58-note manual compass as the standard, along with a 30-note compass for the pedal. You can still find 27-note pedals on small instruments, but the 58-note manual compass was standard on organs both large and small. In the last decade of the nineteenth century, with the adoption of electric actions, you will see the first instances of 61-note manuals and 32-note pedals. However, even when manuals were full compass, divided stops were common on smaller instruments, and you will find the "Unison Bass" on the stoplists of many dispositions. The practice of dividing a single rank so that the first twelve pipes played from a separate stop allowed those pipes -- usually stopped, and often wooden -- to serve as the bottom octave of more than one rank of pipes. This practice allowed some savings in construction, because the larger pipes of one rank wouldn't be needed, as well as more economic use of space that was often limited. Although some builders simply provided a channel so that the pipes were played by either of two stops, the common practice on Hook organs was to provide a separate knob for the first twelve pipes. This provision for flexibility in small organ design was even extended to the reeds, something you can see in the "Bassoon/Oboe" stops of small Hooks of the late nineteenth century. Tonal CharacteristicsWhen you hear a late nineteenth-century organ, you can find another way that builders emphasized the fundamental in their instruments. In general, principals and flutes were built to larger scales, so that they produced more sound. Increased wind pressures and modified voicing -- especially increased nicking -- resulted in louder, more fundamental sounds from these pipes. In the last quarter of the century, Hook & Hastings were among the more conservative builders in this regard, and they retained traditional scales and voicing for a longer time than did many of their competitors. As you have the opportunity to visit some instruments of this period, make it a special point to listen to the sound of the 8' Open Diapason alone. This is the most important indication you can find of the general tonal characteristics of any instrument, of course, and by listening first to this stop, you can prepare yourself for the sounds of the rest of the organ. You will find those by Hook to be noticeably brighter and richer than Diapasons made by most other builders during the same time period. Even though the basic chorus stops were moving in the direction of larger scales and a more fundamental sound, strings and reeds were built with another tonal goal in mind. Strings were being built with smaller scales in an effort to produce a higher overtone to fundamental ratio and thus more penetrating sounds. The gentleness of older Viols was replaced with sounds that were modeled on those of a French Gambe. By the end of the century, American builders were making a variety of string stops, most of them meant to imitate more closely the sound of the modern string ensemble or orchestra. Reeds, too, were made to more closely imitate the sounds of their orchestral counterparts, and some of them -- such as the "Orchestral Oboe" -- even had names that indicated the builders intention. As they had done earlier in the century, the Hooks published several advertising brochures during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, most of which contain the expected testimonials and quotations from satisfied clients or from the press. One of the most impressive of these publications was issued following the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia -- a grand event that combined everything you probably remember from a State Fair with everything a buyer would expect to find in a modern trade show. Along with other builders, Hook & Hastings had an exhibit there, in which they presented to the public the best of their current product -- in this case several small organs and a grand four-manual instrument. The brochure was published in the following year, allowing them to publicize their grand industrial success in their fiftieth year of operation. You might even call it a "golden opportunity" for self-congratulation. Some of the comments in the brochure are unattributed, even when they are purported to be from people not connected with the firm. It does contain, however, this description of the sound of the instrument as a quotation from the Judges' Award to the firm:235 "Its foundation registers are rich and far reaching in tone, of a pure diapason quality and of excellent qualifying power, the tones of the 4 ft., the 2 ft. and mixtures are brilliant without shrillness, the reeds full and resonant. The italicized words in the brochure -- reproduced above -- give us a good indication of the qualities of sound that were considered desirable. As you read the details of late nineteenth century organs by Hook and other builders, and -- more importantly -- as you play some of these instruments, pay attention to the sounds both of individual stops and of ensembles and evaluate them in terms of these descriptions. When you have the opportunity to do so, listen to the individual stops of the principal chorus in this way.

It was this exaggeration of the traditional balance within the chorus that gave these instruments their "power without shrillness." The relative "smoothness" of sound, created by a decrease in upper harmonics within individual voices, also contributed to the "solemn" quality of tone, as it simultaneously aided the blending of disparate 8' registers. Both of these characteristics of late nineteenth-century organs contributed to their continued success in an era that saw more and more opportunities for the instrument to be heard in a variety of locations playing an increasingly varied repertoire. Mechanical CharacteristicsIn the last half of the nineteenth century, the Hooks continued to build small organs with strictly mechanical action. "Manual labor," if you will, powered the bellows, drew the stops, and pressed the keys. Larger instrument, however, were outfitted with some form of pneumatic assistance, either in the form of Barker levers or through the use of tubular pneumatic action. Both of these systems were based on the principle of harnessing wind power to move parts of the action, but they applied the principle in different ways. In the Barker lever, rigid trackers conveyed the motion from a small pallet to a larger one; in tubular pneumatic actions, the small pallet admitted wind to a conduit -- the "tube." At the other end of the tube -- which could be at some distance away, and not in a straight line -- that wind opened another pallet. The use of either system meant that less energy was required by the player to draw or retire a stop, or to press a key. As wind pressures increased, or as instruments became larger, these pneumatic assists were more important, and more frequently employed.

These mechanical innovations meant that detached consoles could be built more easily, that larger instruments could be played more easily, and that divisions on higher pressures could be employed more freely. Although they were certainly not the first builder to do so, Hook built its first instruments with electric action in the last decade of the nineteenth century. That particular mechanical development of course made both separation of the console from the instrument and playing it much easier. No longer was the console tied to the instrument by rigid trackers -- flexible wiring did the job. Both the console and the player would soon leave the organ and move to a separate location because of this innovation in the mechanics of the organ, but the journey would wait until the twentieth century to be completed. AppearanceThe appearance of organs in the United States changed dramatically during the late nineteenth century. Case designs of the earlier part of the century reflected different architectural styles and gave the instruments a flexibility that was unified by their omnipresence. The case was an inseparable part of the instrument, an important part of its visual identity. The consistent element of a free-standing case, enfolding the instrument within it walls, was soon reduced, however, to a mere framework -- one whose life span was short as it too made way for free-standing pipes that appeared to stand above a lower framework without visible means of support.

Of course, the pipes are actually supported both by the rack board in which they are standing and by a frame that is hidden behind the them -- they aren't really floating freely above the toe-board. In some cases interior pipes were visible between the façade pipes, but often these were obscured by cloth fastened to the framework, behind the pipes, so that only the highly decorated pipes were visible. Organs by Hook & Hastings, though colorful, were conservative in their stencilled pipe displays in comparison to some by other builders. As you look at the photographs on pages devoted to specific American instruments, pay attention to the appearance of each one. Even though this type of decoration has long been out of favor, it is an important aspect of the late nineteenth-century organ in the United States. © 2001 AD James H. Cook |

Another form of assistance in actions is found in the application of hydraulic power to the problem of raising enough wind for a large instrument. When you think about it, this was a crucial issue in the late nineteenth century. Large instruments, large scales, large sounds -- they all required large amounts of wind. Of course, instruments could be built with multiple bellows, requiring several people to pump them, but that meant the organist had to employ several people each time he or she needed to play. During the last half of the century, several firms developed "water engines," essentially adaptations of the principle of the water wheel, to provide this auxiliary power.

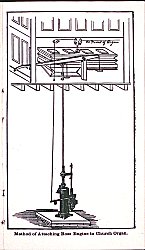

Another form of assistance in actions is found in the application of hydraulic power to the problem of raising enough wind for a large instrument. When you think about it, this was a crucial issue in the late nineteenth century. Large instruments, large scales, large sounds -- they all required large amounts of wind. Of course, instruments could be built with multiple bellows, requiring several people to pump them, but that meant the organist had to employ several people each time he or she needed to play. During the last half of the century, several firms developed "water engines," essentially adaptations of the principle of the water wheel, to provide this auxiliary power.  The photograph to the left is of the cover of a brochure advertising the Ross Water Engine, a solution to the wind problem used by the Hooks and other firms during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These motors used hydraulic power to operate the bellows, making it unnecessary to have a person pumping the organ at all. The diagram to the right -- from the same brochure -- shows the way the motor was connected to the organ. This method allowed either the water engine or the traditional "pump handle" to be used when the organ was played.

The photograph to the left is of the cover of a brochure advertising the Ross Water Engine, a solution to the wind problem used by the Hooks and other firms during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These motors used hydraulic power to operate the bellows, making it unnecessary to have a person pumping the organ at all. The diagram to the right -- from the same brochure -- shows the way the motor was connected to the organ. This method allowed either the water engine or the traditional "pump handle" to be used when the organ was played.