The Church and the Organ Case

The Church of St. Sulpice is almost unique in Paris. The present building, the latest of a series of churches serving the parish, was completed in the middle of the eighteenth century, not long before the revolution. As you can see in the photograph of the altar and the apse, the interior contains the classical arches and proportions seen in the façade. The Church of St. Sulpice is almost unique in Paris. The present building, the latest of a series of churches serving the parish, was completed in the middle of the eighteenth century, not long before the revolution. As you can see in the photograph of the altar and the apse, the interior contains the classical arches and proportions seen in the façade.

The next time you're in Paris, make it a point to visit the church and the organ. It's worth the trip not only to hear the instrument, but also to see the harmonious blending of building and case. You see, the organ case was designed not by the original organ builder -- Clicquot -- but by the architect -- Chalgrin. This is a rare instance of harmony of design that you should notice as you look around the building -- before you go into the organ loft.

Look at this photograph of the grand orgue. It remains in appearance much as Clicquot built it. You can see some traditional French elements. Move your mouse pointer over the photograph to get a closer look if you'd like. There is a Positif case, for example, and all the pipes of the main case do indeed stand at the same level. But the design is lacking the arrangement of flats and towers, the pinnacles and ornaments that in a traditional case would give it the silhouette of a French chateau. Instead, there is a curved façade, a new symmetrical arrangement of same-sized "flats" (filled with pipes that appear to be identical in size), and an abundance of statues placed before the mouths of the pipes. (We won't mention the clock.) The columns in the façade have the same capitals as the columns of the buildings itself -- icanthus leaves, which you probably remember from the fifth grade as "Corinthian." On the whole, the case presents an imposing sight from the nave, one of great weight and solidity. Look at this photograph of the grand orgue. It remains in appearance much as Clicquot built it. You can see some traditional French elements. Move your mouse pointer over the photograph to get a closer look if you'd like. There is a Positif case, for example, and all the pipes of the main case do indeed stand at the same level. But the design is lacking the arrangement of flats and towers, the pinnacles and ornaments that in a traditional case would give it the silhouette of a French chateau. Instead, there is a curved façade, a new symmetrical arrangement of same-sized "flats" (filled with pipes that appear to be identical in size), and an abundance of statues placed before the mouths of the pipes. (We won't mention the clock.) The columns in the façade have the same capitals as the columns of the buildings itself -- icanthus leaves, which you probably remember from the fifth grade as "Corinthian." On the whole, the case presents an imposing sight from the nave, one of great weight and solidity.

The Organ's Past

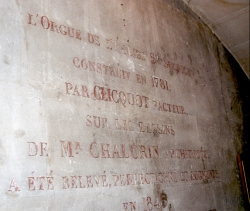

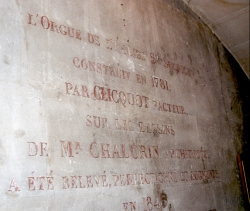

After you leave the nave and go into the gallery, you'll pass a wall with some inscriptions you really should read.240 They describe the history of the organ -- which you are standing under when you look at the wall. They're difficult to photograph, so you'll get a much better look in person. The first inscription says the organ was built in 1781 by Cliquot, to a design of Monsieur Chalgrin, architect. After you leave the nave and go into the gallery, you'll pass a wall with some inscriptions you really should read.240 They describe the history of the organ -- which you are standing under when you look at the wall. They're difficult to photograph, so you'll get a much better look in person. The first inscription says the organ was built in 1781 by Cliquot, to a design of Monsieur Chalgrin, architect.

You'll also see additional tributes to other builders, incuding Daublaine-Callinet and Ducroquet, and recognition that some of their work was done under the direction of Mr. Barker. It's an interesting bit of history to note that Barker had ended his association with Cavaillé-Coll after only a few years. He attempted to form business arrangements with other builders, but failed, eventually returning to England. This notice on the wall of St. Sulpice is one of the few places you will find his name recorded in France.

But -- in  spite of the historical novelty of reading Mr. Barker's name, that's not the most important thing to notice. You really need to read the final inscription in this list. It states that the organ was rebuilt from 1857 to 1862 by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. That's the organ you've come to this church to hear. After its completion in 1862, it was enlarged slightly a few times, the greatest changes being made at the request of Widor, who played the instrument from 1870 until 1933. On the whole, however, when you hear this organ, you are hearing it as Cavaillé-Coll left it. Mechanically and musically, it is one of his greatest instruments, and a monument to his work. spite of the historical novelty of reading Mr. Barker's name, that's not the most important thing to notice. You really need to read the final inscription in this list. It states that the organ was rebuilt from 1857 to 1862 by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. That's the organ you've come to this church to hear. After its completion in 1862, it was enlarged slightly a few times, the greatest changes being made at the request of Widor, who played the instrument from 1870 until 1933. On the whole, however, when you hear this organ, you are hearing it as Cavaillé-Coll left it. Mechanically and musically, it is one of his greatest instruments, and a monument to his work.

The Console

When you reach the tribune, one of the first things you'll notice is the console. It's tucked into the space that originally held the Positif division. All that's left of that is the façade. Cavaillé-Coll's console is a massive thing, with five manuals, curved jambs, and stop knobs arranged in horizontal rows. In spite of its size, everything is in easy reach, largely because of the curvature of the jambs and the relatively small stop knobs -- small when compared to many earlier French instruments, that is. When you reach the tribune, one of the first things you'll notice is the console. It's tucked into the space that originally held the Positif division. All that's left of that is the façade. Cavaillé-Coll's console is a massive thing, with five manuals, curved jambs, and stop knobs arranged in horizontal rows. In spite of its size, everything is in easy reach, largely because of the curvature of the jambs and the relatively small stop knobs -- small when compared to many earlier French instruments, that is.

The curved jambs extend downward, as you can see in the photograph to the right. Look at how many controls are there, above the pedal board. If you can't read the labels clearly, pass you mouse pointer over the photograph. Some of the levers control the couplers and some are composition pedals (more about that later). Perhaps the most important one for you to look at now is the expression pedal for the Récit. It's placed to the right of the thirty-note pedalboard, well into the curve of the side of the console. This is not an unusual placement for this type of "trigger" Swell in the middle of the nineteenth century, of course. You can see similar placements on instruments from England and the United States. I want you to remember where this pedal is, though, the next time you play music by Widor or Dupré. They were both organists at St. Sulpice, and this instrument affected their compositions in different ways, and you can understand their music better if you think of this instrument when you are practicing. The curved jambs extend downward, as you can see in the photograph to the right. Look at how many controls are there, above the pedal board. If you can't read the labels clearly, pass you mouse pointer over the photograph. Some of the levers control the couplers and some are composition pedals (more about that later). Perhaps the most important one for you to look at now is the expression pedal for the Récit. It's placed to the right of the thirty-note pedalboard, well into the curve of the side of the console. This is not an unusual placement for this type of "trigger" Swell in the middle of the nineteenth century, of course. You can see similar placements on instruments from England and the United States. I want you to remember where this pedal is, though, the next time you play music by Widor or Dupré. They were both organists at St. Sulpice, and this instrument affected their compositions in different ways, and you can understand their music better if you think of this instrument when you are practicing.

Actually, before you look at anything else, you should take another look at the five manuals -- at least, at the fifth manual. This photograph shows the maker's label above the top keyboard and the "label for that keyboard directly under the label. The label for the fourth keyboard -- the Récit -- is also visible. If you look closely, you can see that these labels are leather strips applied to the wood and that their edges appear to be a bit frayed. In fact, they have been removed and replaced in a different location. Actually, before you look at anything else, you should take another look at the five manuals -- at least, at the fifth manual. This photograph shows the maker's label above the top keyboard and the "label for that keyboard directly under the label. The label for the fourth keyboard -- the Récit -- is also visible. If you look closely, you can see that these labels are leather strips applied to the wood and that their edges appear to be a bit frayed. In fact, they have been removed and replaced in a different location.

Originally the Récit division was played from the top keyboard -- the fifth manual -- and the Solo from the fourth. This unusual arrangement was in large part dictated by the placement of the Récit at the very top of the case. You might not have noticed it when you first looked at the case, but you can clearly see the swell shutters behind the top-most statues of the Chalgrin design. When Cavaillé-Coll built the organ, there wasn't room in the case for that diviison, so he placed it above everything else. Because the chest and pipes were top-most in the physical layout, the Récit was played by the top-most manual. Later in the life of the instrument -- during the time Dupré was organist (1934-1971) -- the connections were changed, so that the Récit is now played by the fourth manual. That's actually enough of a reach for most of us, but I want you to remember its original position when you get to play some of the more athletic movements by Widor.

Disposition

When Cavaillé-Coll completed his work in 1862, the instrument was the largest in France, a distinction it held until the late twentieth century. You've no doubt been struck by the great number of stop knobs you saw in the photograph above, and it is an impressive sight. And after the description of the swapping around of the two divisions played by the uppermost manuals, I suppose that you've at least idly wondered about the first three manuals and the divisions they control. How did the Récit get moved to the fourth manual, much less the fifth? Look at the complete stoplist of the present disposition, then we'll talk.

|

Grand Choeur (I)

C-g'''

|

|

Grand Orgue (II)

C-g'''

|

|

Positif (III)

C-g'''

|

| Salicional |

|

8

|

|

Principal |

|

16

|

|

Violonbasse |

|

16

|

| Octave |

|

8

|

|

Montre |

|

16

|

|

Quintaton |

|

16

|

| Cornet V |

|

|

|

Bourdon |

|

16

|

|

Quintaton |

|

8

|

| Fourniture IV |

|

|

|

Flûte conique |

|

16

|

|

Flûte traversière |

|

8

|

| Plein Jeu IV |

|

|

|

Montre |

|

8

|

|

Salicional |

|

8

|

| Cymbale VI |

|

|

|

Diapason |

|

8

|

|

Gambe |

|

8

|

| Bombarde |

|

16

|

|

Bourdon |

|

8

|

|

Unda maris |

|

8

|

| Basson |

|

16

|

|

Flûte à pavillon |

|

8

|

|

Flûte douce |

|

4

|

| 1. Trompette |

|

8

|

|

Flûte traversière |

|

8

|

|

Flûte octaviante |

|

4

|

| 2. Trompette |

|

8

|

|

Flûte harmonique |

|

8

|

|

Dulciane |

|

4

|

| Basson |

|

8

|

|

Quinte |

|

5 1/3

|

|

*Quinte |

|

2 2/3 |

| Clairon |

|

4

|

|

Prestant |

|

4

|

|

*Doublette |

|

2

|

| Clairon Doublette |

|

2

|

|

Doublette |

|

2

|

|

*Tierce |

|

1 3/5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

*Larigot |

|

1 1/3

|

|

Récit Expressif (IV)

C-g'''

|

|

|

|

|

|

Piccolo |

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

|

*Plein Jeu III-VI |

|

16

|

| Quintaton |

|

16

|

|

Solo (V)

C-g'''

|

|

*Basson |

|

16

|

| *Diapason |

|

8

|

|

|

*Trompette |

|

8

|

| *Flûte harmonique |

|

8

|

|

Bourdon |

|

16

|

|

*Baryton |

|

8

|

| *Violoncelle |

|

8

|

|

Flûte conique |

|

16

|

|

*Clairon |

|

4

|

| Bourdon |

|

8

|

|

Principal |

|

8

|

|

|

|

|

| Voix céleste |

|

8

|

|

Violoncelle |

|

8

|

|

|

|

|

| Prestant |

|

4

|

|

Gambe |

|

8

|

|

Pedale

C-f'

|

| *Dulciana |

|

4

|

|

Kéraulophone |

|

8

|

|

| *Flûte octaviante |

|

4

|

|

Flûte harmonique |

|

8

|

|

Principal |

|

32

|

| *Nazard |

|

2 2/3

|

|

Bourdon |

|

8

|

|

Principal |

|

16

|

| Doublette |

|

2

|

|

*Quinte |

|

5 1/3

|

|

Contrebasse |

|

16

|

| *Octavin |

|

2

|

|

Prestant |

|

4

|

|

Soubasse |

|

16

|

| Fourniture V |

|

|

|

*Octave |

|

4

|

|

Principal |

|

8

|

| Cymbale IV |

|

|

|

*Flûte octaviante |

|

4

|

|

Violoncelle |

|

8

|

| *Cornet V |

|

|

|

*Tierce |

|

3 1/5

|

|

Flûte |

|

8

|

| *Bombarde |

|

16

|

|

*Quinte |

|

2 2/3

|

|

Flûte |

|

4

|

| *Trompette |

|

8

|

|

*Septième |

|

2 2/7 |

|

*Bombarde |

|

32

|

| Cromorne |

|

8

|

|

*Octavin |

|

2

|

|

*Bombarde |

|

16

|

| Basson Hautbois |

|

8

|

|

*Cornet V |

|

|

|

*Basson |

|

16

|

| Voix humaine |

|

8

|

|

*Bombarde |

|

16

|

|

*Trompette |

|

8

|

| *Clairon |

|

4

|

|

*Trompette |

|

8

|

|

*Ophicléide |

|

8

|

| Trémolo |

|

|

|

*Clairon |

|

4

|

|

*Clairon |

|

4

|

| Machine à grêle |

|

|

|

Trompette Chamade |

|

8

|

|

|

|

|

| Rossignol |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pédales de Combinaison |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tirasses: Grand-choeur, Grand-Orgue, Positif, Récit |

|

*Appels de Jeux de combinaisons |

|

5 appels pour tous les jeux des claviers |

|

Octaves graves pour les cinq claviers manuels |

|

Appel Grand-Choeur |

|

Accomplements: |

|

|

Grand-Choeur au Grand Orgue |

|

|

|

|

|

Grand Orgue au Grand Choeur |

|

|

|

|

|

Positif au Grand Choeur |

|

|

|

|

|

Récit au Grand Choeur |

|

|

|

|

|

Solo au Grand Choeur |

|

|

|

|

|

Récit au Positif |

|

|

|

|

Trompette Chamade |

Quite a list isn't it? We could spend a full class talking about this instrument, its history, its unique features, the way Cavaillé-Coll used existing pipes in his design -- on and on. But, in the interest of finishing the course before the end of the term, I'll just ask you to notice a few specific things.

First of all, let's re-state the question posed above: what are the five manual divisions, and how do they relate to one another and to the usual Cavaillé-Coll model. This is actually a two-part question, sort of what you would expect from a press conference. The first division, played by the first manual, is called the "Grand Choeur," and to really understand it, you need to compare its stops with those of the Grand Orgue. You see, this whole division has the stops that on another instrument by Cavaillé-Coll would be on the laye des anches: the reeds and mixtures, with a couple of single-rank flues thrown in for the sake of balance. You can see the reeds and the mounted cornet in the photograph to the left. Instead of a composition pedal to add the prepared reeds to the Grand Orgue, there is a manual coupler that does the same thing. In other words, you could look at these two divisions as a very large Grand Orgue, divided into its two components: laye des fonds and laye des anches. That takes care of one of the "extra" manuals, and the first part of our two-part question. The other "addition" to the three-manual model is a Solo division, which in this case is very large. Cavaillé-Coll had built other instruments with similar divisions; even his first major instrument at St. Denis had a Bombarde division with high-pressure reeds. So -- the five manual divisions have a clear relationship to other instruments you should read about -- if you haven't done so already. First of all, let's re-state the question posed above: what are the five manual divisions, and how do they relate to one another and to the usual Cavaillé-Coll model. This is actually a two-part question, sort of what you would expect from a press conference. The first division, played by the first manual, is called the "Grand Choeur," and to really understand it, you need to compare its stops with those of the Grand Orgue. You see, this whole division has the stops that on another instrument by Cavaillé-Coll would be on the laye des anches: the reeds and mixtures, with a couple of single-rank flues thrown in for the sake of balance. You can see the reeds and the mounted cornet in the photograph to the left. Instead of a composition pedal to add the prepared reeds to the Grand Orgue, there is a manual coupler that does the same thing. In other words, you could look at these two divisions as a very large Grand Orgue, divided into its two components: laye des fonds and laye des anches. That takes care of one of the "extra" manuals, and the first part of our two-part question. The other "addition" to the three-manual model is a Solo division, which in this case is very large. Cavaillé-Coll had built other instruments with similar divisions; even his first major instrument at St. Denis had a Bombarde division with high-pressure reeds. So -- the five manual divisions have a clear relationship to other instruments you should read about -- if you haven't done so already.

Before you leave the stoplist, I also want you to notice some specific stops, and for the sake of conserving both time and space, we'll just look at a few flues, a few reeds, and a couple of unusual items.

In fact, the unusual items might be a good place to start -- at least they're entertaining. Look at the last two stops in the Récit. A Rossignol, as you no doubt know, is a nightingale, a stop that imitates bird song sounds through pipes that burble up through a liquid. You will find similar stops on other French instruments, as well as on Italian organs, where they are called Ussignoli. The Machine à grêle is another matter, however, one you are less likely to encounter on other instruments today. It purpose was to provide the sounds of hailstones during the "storm" improvisations that were popular when Lefébure-Wély, the brilliant nineteenth-century performer, was named as the first organist of the new instrument. As you can see in the photograph, this "machine" was a complicated-looking affair. In fact, it's a rather simple concept: A metal and leather drum containing stones is rotated when the stop is drawn. As the stone bump around a rattle against the drum, they make a sound like that of hail striking a roof. A very effective "special effect" for those improvisations. In fact, the unusual items might be a good place to start -- at least they're entertaining. Look at the last two stops in the Récit. A Rossignol, as you no doubt know, is a nightingale, a stop that imitates bird song sounds through pipes that burble up through a liquid. You will find similar stops on other French instruments, as well as on Italian organs, where they are called Ussignoli. The Machine à grêle is another matter, however, one you are less likely to encounter on other instruments today. It purpose was to provide the sounds of hailstones during the "storm" improvisations that were popular when Lefébure-Wély, the brilliant nineteenth-century performer, was named as the first organist of the new instrument. As you can see in the photograph, this "machine" was a complicated-looking affair. In fact, it's a rather simple concept: A metal and leather drum containing stones is rotated when the stop is drawn. As the stone bump around a rattle against the drum, they make a sound like that of hail striking a roof. A very effective "special effect" for those improvisations.

Some of the stops -- the "normal" stops that use sounding pipes -- might also have names you are not accustomed to seeing. In some cases, these stops added earlier in the nineteenth-century, so you can think of them as part of the nineteenth-century French organ apart from the Cavaillé-Coll tradition. The Flûte à pavillon, for example, was one of those "experimental" open flutes popular in the early nineteenth century. The top portion of its cylindrical resonator is a sharply flared cone. Only a few French instruments contain a stop of this type, and ths same can be said of the Kéraulophone, a string on the Solo. Both of these unusual stops were retained by Cavaillé-Coll from the work done by his predecessors in "revising" the original Clicquot organ.

As is the case with the flues, there are also some interesting reeds. The Cromorne -- not the Clarinette you would expect on a nineteenth-century organ -- is retained from the original Clicquot, although it has been moved to the Récit from the Positif. Actually quite a few reeds, including the Voix humaine (moved from the Grand orgue to the Récit), the 16' Bombarde, the Trompette and the Clairon in the Pédale are eighteenth-century stops built by Cliquot. The Trompette Chamade, however, is a Cavaillé-Coll addition, but unlike most stops of this name, it's not a prominently displayed horizontal reed. Instead, as you see in the photograph, it's a hooded trumpet, projecting its sound directly into the room from a prominent position high in the front section of the case. As is the case with the flues, there are also some interesting reeds. The Cromorne -- not the Clarinette you would expect on a nineteenth-century organ -- is retained from the original Clicquot, although it has been moved to the Récit from the Positif. Actually quite a few reeds, including the Voix humaine (moved from the Grand orgue to the Récit), the 16' Bombarde, the Trompette and the Clairon in the Pédale are eighteenth-century stops built by Cliquot. The Trompette Chamade, however, is a Cavaillé-Coll addition, but unlike most stops of this name, it's not a prominently displayed horizontal reed. Instead, as you see in the photograph, it's a hooded trumpet, projecting its sound directly into the room from a prominent position high in the front section of the case.

Enlarged Images

If you would like to see enlargments of some of the photographs on this page, you can choose from the selections below. You will have to use the "back" button on your browser to return to this page.

The extremely large size of some of these images means that loading them will take an unduly long time if you are viewing these pages through a modem connection.

|

The Church of St. Sulpice is almost unique in Paris. The present building, the latest of a series of churches serving the parish, was completed in the middle of the eighteenth century, not long before the revolution. As you can see in the photograph of the altar and the apse, the interior contains the classical arches and proportions seen in the façade.

The Church of St. Sulpice is almost unique in Paris. The present building, the latest of a series of churches serving the parish, was completed in the middle of the eighteenth century, not long before the revolution. As you can see in the photograph of the altar and the apse, the interior contains the classical arches and proportions seen in the façade.

After you leave the nave and go into the gallery, you'll pass a wall with some inscriptions you really should read.

After you leave the nave and go into the gallery, you'll pass a wall with some inscriptions you really should read. spite of the historical novelty of reading Mr. Barker's name, that's not the most important thing to notice. You really need to read the final inscription in this list. It states that the organ was rebuilt from 1857 to 1862 by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. That's the organ you've come to this church to hear. After its completion in 1862, it was enlarged slightly a few times, the greatest changes being made at the request of Widor, who played the instrument from 1870 until 1933. On the whole, however, when you hear this organ, you are hearing it as Cavaillé-Coll left it. Mechanically and musically, it is one of his greatest instruments, and a monument to his work.

spite of the historical novelty of reading Mr. Barker's name, that's not the most important thing to notice. You really need to read the final inscription in this list. It states that the organ was rebuilt from 1857 to 1862 by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. That's the organ you've come to this church to hear. After its completion in 1862, it was enlarged slightly a few times, the greatest changes being made at the request of Widor, who played the instrument from 1870 until 1933. On the whole, however, when you hear this organ, you are hearing it as Cavaillé-Coll left it. Mechanically and musically, it is one of his greatest instruments, and a monument to his work. When you reach the tribune, one of the first things you'll notice is the console. It's tucked into the space that originally held the Positif division. All that's left of that is the façade. Cavaillé-Coll's console is a massive thing, with five manuals, curved jambs, and stop knobs arranged in horizontal rows. In spite of its size, everything is in easy reach, largely because of the curvature of the jambs and the relatively small stop knobs -- small when compared to many earlier French instruments, that is.

When you reach the tribune, one of the first things you'll notice is the console. It's tucked into the space that originally held the Positif division. All that's left of that is the façade. Cavaillé-Coll's console is a massive thing, with five manuals, curved jambs, and stop knobs arranged in horizontal rows. In spite of its size, everything is in easy reach, largely because of the curvature of the jambs and the relatively small stop knobs -- small when compared to many earlier French instruments, that is.

Actually, before you look at anything else, you should take another look at the five manuals -- at least, at the fifth manual. This photograph shows the maker's label above the top keyboard and the "label for that keyboard directly under the label. The label for the fourth keyboard -- the Récit -- is also visible. If you look closely, you can see that these labels are leather strips applied to the wood and that their edges appear to be a bit frayed. In fact, they have been removed and replaced in a different location.

Actually, before you look at anything else, you should take another look at the five manuals -- at least, at the fifth manual. This photograph shows the maker's label above the top keyboard and the "label for that keyboard directly under the label. The label for the fourth keyboard -- the Récit -- is also visible. If you look closely, you can see that these labels are leather strips applied to the wood and that their edges appear to be a bit frayed. In fact, they have been removed and replaced in a different location. First of all, let's re-state the question posed above: what are the five manual divisions, and how do they relate to one another and to the usual Cavaillé-Coll model. This is actually a two-part question, sort of what you would expect from a press conference. The first division, played by the first manual, is called the "Grand Choeur," and to really understand it, you need to compare its stops with those of the Grand Orgue. You see, this whole division has the stops that on another instrument by Cavaillé-Coll would be on the laye des anches: the reeds and mixtures, with a couple of single-rank flues thrown in for the sake of balance. You can see the reeds and the mounted cornet in the photograph to the left. Instead of a composition pedal to add the prepared reeds to the Grand Orgue, there is a manual coupler that does the same thing. In other words, you could look at these two divisions as a very large Grand Orgue, divided into its two components: laye des fonds and laye des anches. That takes care of one of the "extra" manuals, and the first part of our two-part question. The other "addition" to the three-manual model is a Solo division, which in this case is very large. Cavaillé-Coll had built other instruments with similar divisions; even his first major instrument at St. Denis had a Bombarde division with high-pressure reeds. So -- the five manual divisions have a clear relationship to other instruments you should read about -- if you haven't done so already.

First of all, let's re-state the question posed above: what are the five manual divisions, and how do they relate to one another and to the usual Cavaillé-Coll model. This is actually a two-part question, sort of what you would expect from a press conference. The first division, played by the first manual, is called the "Grand Choeur," and to really understand it, you need to compare its stops with those of the Grand Orgue. You see, this whole division has the stops that on another instrument by Cavaillé-Coll would be on the laye des anches: the reeds and mixtures, with a couple of single-rank flues thrown in for the sake of balance. You can see the reeds and the mounted cornet in the photograph to the left. Instead of a composition pedal to add the prepared reeds to the Grand Orgue, there is a manual coupler that does the same thing. In other words, you could look at these two divisions as a very large Grand Orgue, divided into its two components: laye des fonds and laye des anches. That takes care of one of the "extra" manuals, and the first part of our two-part question. The other "addition" to the three-manual model is a Solo division, which in this case is very large. Cavaillé-Coll had built other instruments with similar divisions; even his first major instrument at St. Denis had a Bombarde division with high-pressure reeds. So -- the five manual divisions have a clear relationship to other instruments you should read about -- if you haven't done so already. In fact, the unusual items might be a good place to start -- at least they're entertaining. Look at the last two stops in the Récit. A Rossignol, as you no doubt know, is a nightingale, a stop that imitates bird song sounds through pipes that burble up through a liquid. You will find similar stops on other French instruments, as well as on Italian organs, where they are called Ussignoli. The Machine à grêle is another matter, however, one you are less likely to encounter on other instruments today. It purpose was to provide the sounds of hailstones during the "storm" improvisations that were popular when Lefébure-Wély, the brilliant nineteenth-century performer, was named as the first organist of the new instrument. As you can see in the photograph, this "machine" was a complicated-looking affair. In fact, it's a rather simple concept: A metal and leather drum containing stones is rotated when the stop is drawn. As the stone bump around a rattle against the drum, they make a sound like that of hail striking a roof. A very effective "special effect" for those improvisations.

In fact, the unusual items might be a good place to start -- at least they're entertaining. Look at the last two stops in the Récit. A Rossignol, as you no doubt know, is a nightingale, a stop that imitates bird song sounds through pipes that burble up through a liquid. You will find similar stops on other French instruments, as well as on Italian organs, where they are called Ussignoli. The Machine à grêle is another matter, however, one you are less likely to encounter on other instruments today. It purpose was to provide the sounds of hailstones during the "storm" improvisations that were popular when Lefébure-Wély, the brilliant nineteenth-century performer, was named as the first organist of the new instrument. As you can see in the photograph, this "machine" was a complicated-looking affair. In fact, it's a rather simple concept: A metal and leather drum containing stones is rotated when the stop is drawn. As the stone bump around a rattle against the drum, they make a sound like that of hail striking a roof. A very effective "special effect" for those improvisations. As is the case with the flues, there are also some interesting reeds. The Cromorne -- not the Clarinette you would expect on a nineteenth-century organ -- is retained from the original Clicquot, although it has been moved to the Récit from the Positif. Actually quite a few reeds, including the Voix humaine (moved from the Grand orgue to the Récit), the 16' Bombarde, the Trompette and the Clairon in the Pédale are eighteenth-century stops built by Cliquot. The Trompette Chamade, however, is a Cavaillé-Coll addition, but unlike most stops of this name, it's not a prominently displayed horizontal reed. Instead, as you see in the photograph, it's a hooded trumpet, projecting its sound directly into the room from a prominent position high in the front section of the case.

As is the case with the flues, there are also some interesting reeds. The Cromorne -- not the Clarinette you would expect on a nineteenth-century organ -- is retained from the original Clicquot, although it has been moved to the Récit from the Positif. Actually quite a few reeds, including the Voix humaine (moved from the Grand orgue to the Récit), the 16' Bombarde, the Trompette and the Clairon in the Pédale are eighteenth-century stops built by Cliquot. The Trompette Chamade, however, is a Cavaillé-Coll addition, but unlike most stops of this name, it's not a prominently displayed horizontal reed. Instead, as you see in the photograph, it's a hooded trumpet, projecting its sound directly into the room from a prominent position high in the front section of the case.